Seatbelts save lives. They are mandatory in cars and most coaches, so why not on urban buses? The answer lies in the intersection of engineering, behaviour, cost, and everyday practicality.

UK urban buses are deliberately designed to prioritise capacity, accessibility and speed. They are built to move large numbers of people short distances in dense environments. Passengers stand, move to the doors, squeeze past one another, and hop off every few minutes. As such, they are legally exempt from the government’s seatbelt requirements.

Mandating belts for every seat would run headlong into the realities of urban bus travel. How could operators enforce seatbelt use on a vehicle where people may be standing? How much slower would boarding become if every seated passenger had to buckle in before the vehicle could move? And who would pay for the retrofitting of thousands of vehicles at a high cost?

These are not simply logistical quibbles but are core considerations in a system where reliability and frequency are key pillars for a successful public transport network.

Would Seatbelts Make Urban Buses Safer?

Safety remains a vital consideration for all modes of transportation. But urban buses operate in conditions fundamentally different from high-speed coaches, where the most catastrophic crashes involving rollovers and high-energy impacts are more likely.

Urban collisions happen, and are sometimes serious, but the majority involve low-speed impacts where the risk profile is very different to high-speed motorway traffic. For decades, bus interiors have been engineered around ‘compartmentalisation’ with heavily padded, closely spaced seating designed to absorb impact forces without relying on restraints. This approach has performed well enough that there has never been strong evidence to justify a wholesale shift in design philosophy.

This does not mean risks are negligible, nor that seatbelts offer no benefit. They can help prevent upper-deck passengers from being thrown forward in a sudden stop and may reduce injuries in certain types of collisions. However, the question remains whether they deliver meaningful benefits in practice.

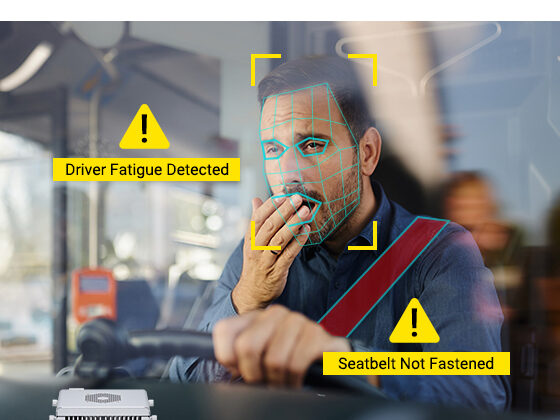

Indeed, even where seatbelts are fitted, such as on long-distance buses, use is inconsistent. Passengers often ignore them, remove them mid-journey, or struggle with belts that are jammed, dirty, or poorly maintained. If compliance is low on services with long journeys, expecting high compliance on short-hop city routes is unrealistic.

Introducing seatbelts on urban buses may therefore create a system that is marketed as a safety improvement, but delivers little positive change.

As a result, the case for seatbelts on UK urban buses remains weak, because the design, operation, and risk profile of these vehicles make seatbelts a poor fit for the task. The smartest policy is not the one that sounds safest, but the one that delivers real safety benefits in the real world.

Urban buses should continue to be designed around safe, efficient movement, and the focus should remain on the measures that truly reduce risk, rather than those that simply feel like they should.