Multi-operator DRT services can make buses accessible to more people and drive down per-passenger subsidies, but barriers exist.

Bus economics necessitate difficult questions. Whilst efficient corridor routes have been optimised and finely tuned to ensure profitability, networks which reach into communities at a more granular level, are, almost by definition, impossible to configure as high capacity, high volume services. On this level, demand responsive transport (DRT) offers an efficient way of creating a bus network.

However, there’s no evidence of lavish subsidies in the offing, so it too comes with its own set of questions: Where can DRT drive up patronage, so that the per passenger subsidy goes down? How can we reduce vehicle numbers to ensure that the fleet is efficient? And how can we combine operators and services available to ensure that all capacity is utilised?

It’s not just a question of subsidy, either. Duplicate vehicles and parallel services are all eating into our limited carbon budget. We need to ensure that services are both financially and emissions efficient. The variables at play here are passenger groups, vehicle numbers and operators. Optimisation ensures they are combined to ensure that people get to their destinations as needed, whilst using the least resources.

However, in the UK, when we look at bus services, what we see are not so much networks as fragmented services run by assorted operators (and sometimes different types of operators) with multiple funding streams – sometimes duplicating each other – and which may also be providing their services under differently regulated frameworks.

Most visibly, the traditional fixed line bus network comprises an assortment of routes, some of which are run by bus operators ‘for profit’ without local authority intervention, some funded by local authorities, some that are blended versions (for instance with the off-peak subsidised whilst peak services are not).

Then, beyond the ‘traditional public transport’ envelope, there are various forms of community transport which exist in a very different space. In some cases, community transport works similarly to commercial bus services but servicing ‘not for profit’ routes that would not otherwise exist, and others which are more like community coach trips – booked in advance for a round trip to an attraction, shop or service – with yet more that are more akin to low-cost taxis with volunteer drivers taking individuals to appointments.

On top of this we have various different social care transport services, school buses and tailored travel for vulnerable children and adults. Then there are services for NHS patients that often cover very similar catchment areas. A further group of services have emerged serving (largely) out of town business parks – not deemed sufficiently attractive by commercial bus operators – in the form of the modern equivalent of the ‘works bus’: an on-demand shuttle or a taxi sharing app.

If we take an honest (and wide-ranging) look across all areas, there are all sorts of duplications even within funded transport. For instance, there are Ring & Ride-type access services being operated in parallel with DRT services because different funding streams procure different resources. This has been a constant frustration for local authorities. Total Transport pilots tried to address some of these duplication issues and optimise vehicle usage, however it proved difficult to execute sophisticated ideas about fleet optimisation or combining use cases.

Over the last three years, the capability of the technology has come a long way, addressing some of the execution issues. For instance, the Padam Mobility platform is able to combine multiple operators into a single service and sophisticated software has the potential to merge different use cases with one service. It also offers a paratransit software element in order to handle social service and health care transport, providing the right vehicle for the trips needed and optimising the overall fleet management.

In one area DRT is combined with home-to-school transport using the same vehicles reducing the cost of the home-to-school from around £10 per head down to £5. Adding in further deployments to increase utilisation could lower this further. However, if we look at other countries with different regulatory systems, we see more radical combinations.

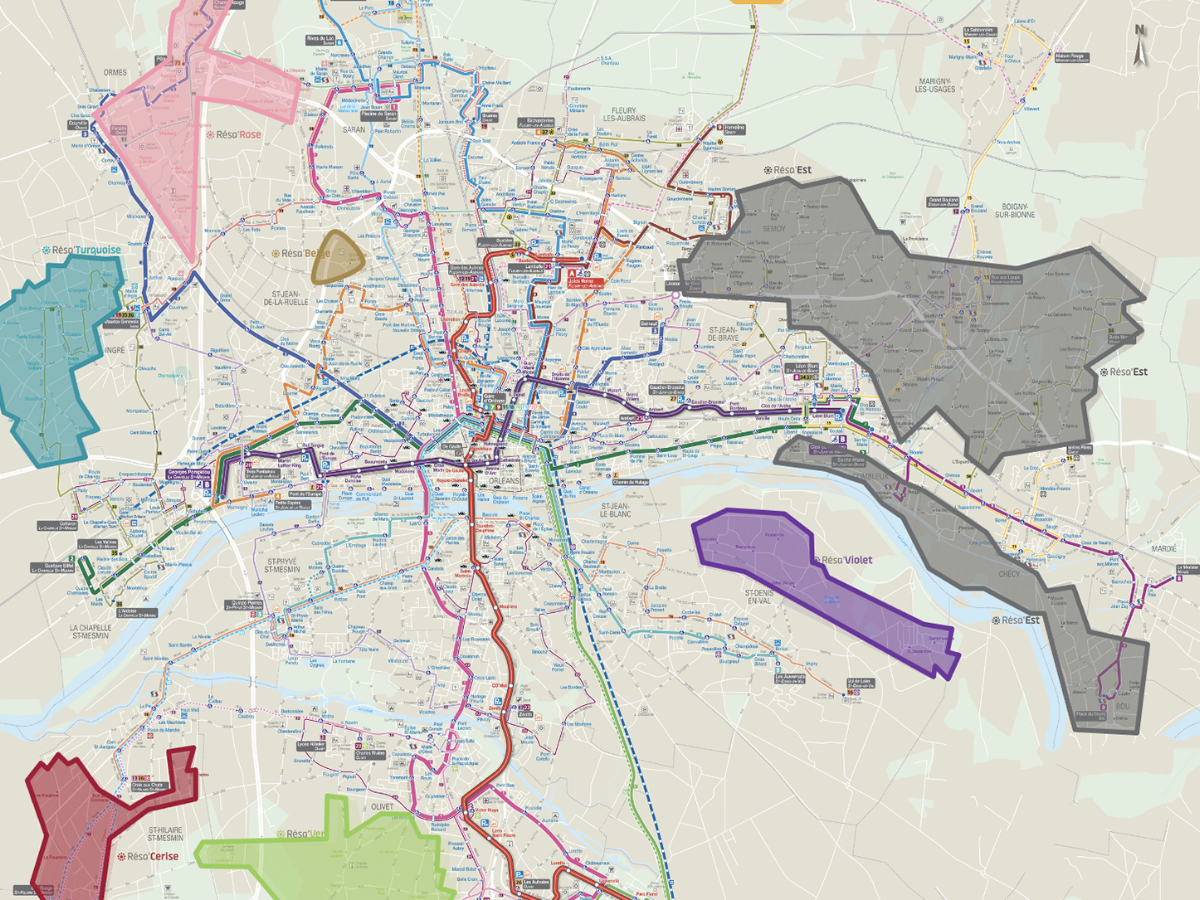

In Strasbourg, Padam Mobility blends door-to-door ‘paratransit’ with bus stop-to-bus stop DRT, using the same fleet. For the Île-de-France Mobilités service which connects people who live on the outer edges of suburbs beyond the Paris metropolitan area Padam Mobility has combined multiple operators onto a single platform. Combining in this way across operators has shown instances where the work of 20 minibuses can now be done by 12, which obviously implies significant savings.

In the UK, however, the technology only takes us so far. Legacy regulation – where each type of services has its own regulatory framework – restricts the potential for combining use cases. These differing frameworks affect many of the aspects of the service: the types of vehicles that can be used, timetables and routes (and how changes must be registered), driver licensing and training requirements, conditions of carriage and the fares that can be charged (and whether they attract VAT).

The final section provides a brief, incomplete overview of these regulations in the UK.

Why Is Regulation an Issue?

The current regulatory framework makes it hard to create simple and pragmatic solutions that enable vehicle use to be maximised and fleets adapted. Once services try to optimise and provide the right size vehicle for the time of day the service could potential segue between regulatory frameworks. A bus service that runs a single decker at peak times, a mini-bus during off-peak and a ‘shared taxi’ to ensure that people working early or late shifts can still get home appears to need more than one type of registration. Adding community services to an on-demand transport platform to help augment off-peak provision would violate the Section 19 registration of a community transport operator (not open to the public) and is a minefield in the case of Section 22 with some operators being challenged over their ‘not for profit’ status in the courts. Some on-demand shared trip services base prices on the number of people riding in order to enable PSV or taxi companies to provide the services and remain profitable – whilst this works in some circumstances it becomes difficult to integrate in the public transport network to augment low density scenarios.

We’ve also found commuter shuttles organised privately for employers often require subsidies from them – whilst also excluding other people travelling along their routes. This is generally because they’re not registered as public bus routes – one factor in that is the time delay that is built into registering with

the traffic commissioner.

Optimise Multi-Operator Services

Whilst it’s increasingly worthwhile to look at how DRT platform technologies can host an efficient cross-contract and multi-user services it’s also important to look at the limitations regulation places on these combinations. A sophisticated DRT platform can potentially manage a service supplied by community transport or even taxis at some times of day whilst moving to a bus operator on a fixed time table at others.

It seems that regulation needs a rethink to make this a manageable process. The costs of not doing so are both financial and in under-utilised assets which means wasting our ever-diminishing carbon budget.

The opportunity, however, where local authorities, operators, businesses and the third sector all work on networks together, is that together we can drive down per passenger subsidies – whilst still improving services and increasing the number of people who have the option to take the bus.

A Short Incomplete Survey of Regulation

Public bus services are registered with the Office of the Traffic Commissioner and must meet certain standards. Following the introduction of the Bus Open Data regulations in 2021, ticket prices for public transport buses must be notified to the secretary of state – in practice this means uploading them through the Department for Transport’s Open Data portal. All public service vehicles (over eight people) need to be fully accessible, regardless of size.

The situation becomes more complex for flexible bus services. Whilst they must register with the Traffic Commissioner they must comply with additional criteria (e.g. “fare information must be clearly displayed”). Flexible services that cover locations more than 15 miles apart (in a straight line) do not qualify for BSOG (Bus Service Operators Grant). There is also a requirement that fares per passenger must be fixed, rather than reducing as more passengers board (in the case that fares reduce if more people share a vehicle that vehicle would be classed as a PHV). Passengers should pre-book but there is no minimum booking time. Passengers who haven’t pre-booked can be carried but the route cannot be altered to accommodate them (because this would then be classed as a taxi service). Whilst bus tickets do not attract VAT, taxi fares do.

Community transport services which are open to the public (Section 22) must register with the Traffic Commissioner. They cannot make a profit unless offering hire services which do not compete with public bus services. In addition, Section 19 Permits can be issued by Local Authorities to organisations operating services for education, religious or community transport purposes for small vehicles such as up to 17 seater minibuses. Larger vehicles must be registered with the Traffic Commissioner. They cannot be open to the public.

Taxi services are registered with local authorities and registration includes agreement on the fares set whilst private hire services are registered with local authorities, which can impose conditions on the type and age of vehicle but has no power to set fares. A maximum of eight passengers can be carried. VAT is payable on fares (although small businesses don’t meet the threshold, private hire apps like Uber do). Whilst bus services have to be fully accessible, a limited number of taxi and private hire services are. As an aside, these conditions vary where services are registered in London, in particular, there is usually an additional requirement to register with Transport for London.

This article was originally written by Beate Kubitz and published by Padam Mobility.